Operation Deadlight was a post-World War II undertaking by the Allies, primarily led by the British Royal Navy, to scuttle over 100 captured German U-boats in the North Atlantic.

Initiated in late 1945 and extending into 1946, the operation involved towing the submarines to a designated area northwest of Ireland, where they were sunk.

The U-Boat Terror

German U-boats, short for Unterseeboot, meaning “undersea boat,” were a critical component of Nazi Germany’s Kriegsmarine (navy) during World War II. Their primary function was to conduct submarine warfare, primarily focusing on the Battle of the Atlantic, which was the struggle for control of the shipping lanes in the North Atlantic.

This battle was crucial because the Allies depended heavily on trans-Atlantic shipping for supplies, military equipment, and personnel from North America to Europe.

The U-boats operated mainly in wolf packs, a tactic that involved groups of submarines attacking merchant convoys at night and attempting to overwhelm the convoy’s escorts.

The strategy was to sink as much Allied shipping as possible, cutting off Britain and the Soviet Union from their overseas resources and thereby crippling their war efforts.

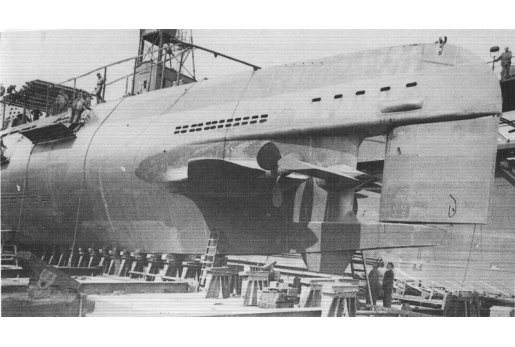

Complete sections (pressure hull with outer skin) of submarine type XXI. Section 8th in the background and probably 7th in the front.

Complete sections (pressure hull with outer skin) of submarine type XXI. Section 8th in the background and probably 7th in the front.

U-boats were highly effective in the early years of the war, thanks to their advanced technologies, including the torpedoes they used and their stealth capabilities. They benefitted from the element of surprise and the lack of effective anti-submarine warfare (ASW) tactics by the Allies at the time.

However, as the war progressed, the Allies developed more sophisticated ASW tactics and technology, such as sonar, radar, improved depth charges, and the breaking of German naval codes.

These advancements, along with increased Allied production of merchant ships and escorts, began to turn the tide against the U-boats.

The U-boat fleet suffered significant losses, especially from 1943 onwards, as the Allies’ improved tactics and technology took their toll. By the end of the war, more than 750 U-boats had been lost, and the U-boat arm of the Kriegsmarine was effectively defeated.

Despite their eventual defeat, U-boats had a significant impact on the early phases of the war and remain a prominent subject of study in naval warfare history.

Background

Operation Deadlight emerged in the context of the immediate post-World War II period, a time when the Allies were grappling with the remnants of the defeated Axis powers’ military capabilities.

The German U-boat fleet, once the scourge of the Atlantic and a symbol of Nazi Germany’s naval prowess, had been effectively neutralized by the war’s end.

With Germany’s surrender in May 1945, the Allied powers, particularly the United Kingdom and the United States, faced the daunting task of deciding the fate of these formidable submarines.

42 U-Boats await their fate while docked in Lisahally, Northern Ireland, June 1942.

42 U-Boats await their fate while docked in Lisahally, Northern Ireland, June 1942.

In the immediate aftermath of the war, around 156 U-boats were captured or surrendered to the Allied forces. These vessels were distributed across various naval bases in the UK and elsewhere. The Allies were initially uncertain about the best course of action.

Options considered included using the submarines for research purposes, distributing them among the Allied navies, or destroying them to prevent their future use in military conflicts.

Operation Deadlight

The Royal Navy faced the enormous task of dealing with the surrendered German U-boats. These submarines were initially gathered at various ports, including Lisahally in Northern Ireland and Loch Ryan in Scotland, for inspection and disarmament.

The core of Operation Deadlight involved towing the U-boats to the designated scuttling area, approximately 100 miles northwest of Ireland, in the deep Atlantic.

A Polish destroyer tows a U-Boats during the operation, November 1945.

A Polish destroyer tows a U-Boats during the operation, November 1945.

This location was strategically chosen for its depth, reducing the risk of the submarines being salvaged or becoming navigational hazards.

Towing was performed by various Allied naval vessels, including tugs and warships. Each U-boat tow presented its challenges, as many were in poor condition and difficult to manage at sea.

The Execution of Operation Deadlight

Once at the designated location, the scuttling of the U-boats was carried out using different methods. Some were to be used as target practise for aerial forces, some were to be sunk using gunfire from naval vessels, but the primary method intended was to use explosive charges. In actuality, however, most ended up being sunk by gunfire.

The operation was not without its challenges. The British Royal Navy had to contend with the Atlantic’s winter weather, which often hampered towing operations. Additionally, the deteriorated state of many U-boats caused 56 to sink prematurely en route to the scuttling area.

The operation lasted from 17 November, 1945, until 11 February, 1945. 116 U-Boats were scuttled out of the original 156 in Allied possession.

The rest were caimed by nations such the Soviet Union or France, alternatively, some were sold or put into museums.

Plans to Raise the U-Boats

The salvage operations of the U-boats sunk during Operation Deadlight touch upon an aspect of post-war history that intertwines technological innovation with the remnants of conflict, centered around the unique characteristic of low-background radiation steel.

This steel, forged before the dawn of the nuclear age, presents a paradox of value, derived not from its strength or durability but from its absence of contamination by the ambient radiation that now permeates our environment.

The onset of the atomic age, marked by the detonation of the first nuclear weapons in 1945, irrevocably altered the global atmospheric background radiation levels. Materials produced before these nuclear tests, like the steel in pre-1945 U-boats, lack this radioactive signature, making them extraordinarily valuable for specific scientific applications.

Instruments that measure very low levels of radiation, such as those used in medical research, particle physics, and environmental monitoring, benefit from construction materials that do not contribute background noise to their sensitive readings.

Low-background steel becomes a critical resource in these fields, offering a purity no longer attainable in materials produced after the mid-20th century.

The U-boats scuttled under Operation Deadlight represent a potentially significant source of this rare steel. However, the practicality of recovering material from these sunken vessels is fraught with challenges.

Type XXI submarines are regarded as the pioneering “true” submarines due to their capability to carry out wartime operations while maintaining a nearly constant state of submersion.

Type XXI submarines are regarded as the pioneering “true” submarines due to their capability to carry out wartime operations while maintaining a nearly constant state of submersion.

Firstly, the technical difficulty and cost of deep-sea salvage operations are considerable. These U-boats lie at depths that make recovery efforts technically complex and financially prohibitive for most scientific endeavors.

Moreover, the condition of the steel after decades underwater, subjected to corrosion and marine encrustation, must be assessed to determine its viability for sensitive applications.

Legal and ethical considerations also come into play. Wartime wrecks are often treated as war graves, protected under international law, which restricts salvage operations.

The respect due to those who lost their lives in these submarines and the potential archaeological value of the sites must be balanced against the scientific value of the materials they contain.

Environmental concerns further complicate salvage efforts. Disturbing these wrecks risks releasing pollutants trapped in the vessels, such as fuel oil, and may disrupt marine ecosystems that have developed around the artificial reefs formed by the sunken U-boats.

Despite these challenges, the allure of low-background steel has prompted exploration into the feasibility of recovering materials from the Operation Deadlight U-boats.

The scarcity of this resource has led to the use of alternative sources of low-background steel, such as pre-nuclear age buildings and other structures, but the demand in scientific research remains high.