The Carroll A. Deering, a five-masted schooner, was found abandoned under mysterious circumstances off the coast of North Carolina in 1921, with its crew vanished and the ship aground on Diamond Shoals.

Despite extensive investigations by the Coast Guard, FBI, and other agencies, no conclusive evidence ever surfaced to explain the crew’s disappearance or the events leading up to the ship’s final, fateful encounter with the notorious “Graveyard of the Atlantic.”.

The Deering’s enigma remains one of the sea’s most enduring maritime mysteries, often cited alongside the legends of the Bermuda Triangle.

Background Of The Carroll A. Deering

The Carroll A. Deering was built during a transitional period in maritime history. The early 20th century was a time of significant change, with the advent of steam power challenging the dominance of sail.

However, the age of sail had not yet ended, particularly for coastal and regional trade where the economics of steam did not always make sense.

Schooners like the Deering were still a common sight on the high seas, especially in trades where the cost-effectiveness of wind power outweighed the speed and reliability of steam.

The Deering was a schooner—a type of sailing ship characterized by the use of fore-and-aft sails on two or more masts, with the aftermost mast (the mainmast) equal to or taller than the foremast.

The schooner rig was known for its agility and relatively easy handling, with a smaller crew requirement compared to other large sailing ships of the time, making it a cost-effective choice for many shipping lines.

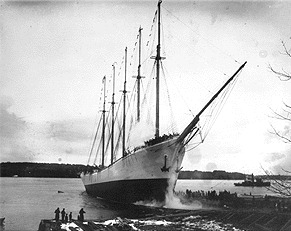

Crafted by the G.G. Deering Company at the turn of the decade, the Carroll A. Deering was constructed at the company’s shipyard in Bath, Maine—a town with a storied shipbuilding history.

Launched in 1919, the Deering measured 255 feet in length and was notable for being one of the last large sailing ships built on the East Coast of the United States.

Her five masts towered above her deck, and she was rigged with a substantial expanse of canvas, allowing her to harness the wind effectively across the vast expanse of the Atlantic.

Launch of the Carroll A. Deering in 1919.

Launch of the Carroll A. Deering in 1919.

The primary role of the Carroll A. Deering was to transport bulk cargo. Her cargo holds were designed to be filled with materials like coal, which was a crucial fuel source during this era, driving the engines of industry and heating the homes of the burgeoning urban populations.

The Deering’s size made her well-suited for this purpose, as she could carry large quantities of cargo with relatively low operational costs.

Coal was a particularly suitable cargo for sailing ships, as it was not time-sensitive like perishable goods and could withstand the longer voyages that wind-powered vessels often took.

The Deering’s voyages from the coal-rich regions of the eastern United States to the ports of South America and back were a part of the global trade routes that fed the industrial demands of the time.

The Fateful Voyage

The Carroll A. Deering was readied for what was intended to be a commonplace commercial expedition. The ship was loaded with coal, a cargo it was designed to carry efficiently, in the bustling docks of Norfolk, Virginia.

It was the summer of 1920, a time when the demand for coal was high, feeding the insatiable engines of industry and the households of both North and South America.

The crew assembled for the voyage were men drawn from the seafaring world, a mixture of seasoned sailors and less experienced hands, all led by Captain William H. Merritt.

The captain was a veteran mariner, selected for his experience and knowledge of the shipping routes the Deering was set to navigate.

In early August 1920, the Carroll A. Deering set sail with the tide, departing the United States for Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

The journey to Brazil would have taken the ship down the Atlantic coast of the U.S., around the treacherous waters of Cape Hatteras, and into the warmer climates of the South Atlantic.

The route was well-traveled and known for its trade winds, which the Deering, with her five masts and full sails, was designed to exploit.

The voyage to Brazil was reportedly uneventful. The ship arrived in Rio de Janeiro to offload its cargo of coal, fulfilling the commercial purpose for which it had been commissioned.

The port call in Rio would have been a bustling time, with the crew engaged in the hard labor of unloading and then taking on provisions for the return trip.

View from the stern of the Carroll A. Deering.

View from the stern of the Carroll A. Deering.

While the details of the ship’s time in Rio are not extensively documented, it is known that an unexpected event occurred: Captain Merritt fell ill. His condition was serious enough that he and his son, the first mate, had to leave the ship.

This left the Deering in need of a new captain and first mate just as it was preparing for its return journey to the United States.

The man chosen to replace Captain Merritt was Captain Willis B. Wormell, a seasoned sailor, though this was his first command of the Deering.

Charles B. McLellan was appointed as the first mate. The swift change in leadership was not unusual for the time but introduced new dynamics into the crew that had not been previously tested on this ship.

The Carroll A. Deering embarked on its return journey to the United States in December 1920. The homeward leg was expected to be relatively straightforward, retracing the Atlantic route back to Norfolk.

The ship was now in ballast, which in maritime terms means it was carrying no cargo, or possibly just enough to provide stability and control.

This would have made the return voyage quicker, as the ship would sit higher in the water and potentially be more susceptible to the wind.

As the Deering made its way back, it encountered other vessels, and it was through these brief maritime encounters that the ship’s progression was logged.

These sightings were the only glimpses into the Deering’s state and the well-being of its crew, as wireless communication was not yet commonplace on commercial sailing vessels.

The last known contact with the Deering came as it passed the Cape Lookout Lightship off the coast of North Carolina on January 31, 1921.

It was during this interaction that a member of the Deering’s crew reported the loss of the ship’s anchors.

This communication was unusual, not only because of the report itself but also because of the behavior of the crew, which seemed uncharacteristically disorganized and agitated.

The Mysterious Abandonment Of The Deering

The final sighting of the Carroll A. Deering, as reported by the keeper of the Cape Lookout Lightship, is the last definitive piece of evidence about the ship’s whereabouts with its crew on board.

It was during this sighting that a crew member, who was not the captain, communicated through a megaphone that the ship had lost its anchors.

The exchange was peculiar for several reasons, not least of which was the fact that someone other than the captain or an officer was speaking—an apparent breach of maritime protocol.

It was not until a few days later, on February 4, 1921, that the Deering would be seen again—this time, found hard aground on Diamond Shoals, an infamous stretch of water off Cape Hatteras, North Carolina, known for its shipwrecks.

The shoals, a series of sandbars that shift with storms and currents, have a storied history as the final resting place for many ships, earning the area the moniker “The Graveyard of the Atlantic.”

When the U.S. Coast Guard reached the stranded schooner, the scene they encountered deepened the mystery.

The ship was discovered to be completely abandoned. The fact that the vessel was not simply adrift but was aground suggested that the crew had been unable to navigate away from the shoals or had abandoned the ship before it ran ashore.

Upon boarding the Carroll A. Deering, the Coast Guard found an eerie tableau. The ship was devoid of its crew but gave few clues as to why or how the abandonment had happened.

The crew’s personal belongings and navigational equipment were missing, which could indicate a hasty evacuation. The ship’s log and navigation records, essential for understanding the ship’s final days, were also gone.

A detail that captured the attention of investigators was the state of the ship’s galley. Reportedly, the stove was still warm, suggesting that the Deering had been abandoned in a hurry.

This detail often gives rise to speculation that whatever prompted the crew to leave occurred suddenly and perhaps unexpectedly.

The Deering seen from the lightship Cape Lookout on 28 January.

The Deering seen from the lightship Cape Lookout on 28 January.

The absence of the ship’s lifeboats was a significant clue. It indicated a deliberate departure rather than a catastrophic event that left no time for an organized evacuation.

This pointed to the possibility that the crew might have left the ship voluntarily or under duress, hoping to reach safety or being forced onto another vessel.

No bodies or survivors were found, and no distress calls had been recorded. The disappearance of the crew without a trace was particularly puzzling given the weather conditions, which had not been reported as especially treacherous in the days leading up to the discovery of the ship.

The warm stove indicated that the ship had likely been abandoned quickly, but not in the middle of immediate disaster, as the crew had time to prepare for departure.

The absence of clear evidence of violence or foul play on the ship raised as many questions as it answered.

Without signs of a struggle or other physical clues, the investigators faced the daunting task of piecing together events with few tangible leads.

In the aftermath of the discovery, the news of the abandoned Deering spread, capturing public imagination and concern.

It became a fixture in the press, with newspapers speculating wildly about what might have befallen the crew. Was it mutiny, piracy, or something more supernatural?

The Coast Guard and later the government inquiries would attempt to reconstruct the final days of the Deering, hoping to solve the puzzle of why a well-found ship with a seasoned captain had been abandoned.

The warm galley stove, the absence of the lifeboats, and the missing logs and navigational instruments hinted at a narrative that has remained elusive, a maritime riddle from an era before modern tracking and communication could have recorded the crew’s fate.

The Investigation

The investigation began with the U.S. Coast Guard, who first boarded the deserted schooner.

Their initial assessments focused on gathering physical evidence from the ship, interviewing the last known people to see the Deering before its abandonment, and examining weather reports and sea conditions during the time of its last voyage.

The Coast Guard’s initial findings were hampered by the lack of a crew to interview and the absence of the ship’s log, which would have provided crucial insights into the Deering’s final days.

Nevertheless, they documented the ship’s condition thoroughly, noting the position of the sails, the state of the galley, and the missing lifeboats.

Due to the mysterious nature of the incident and the possibility of foul play, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) was brought into the case.

The FBI delved into the backgrounds of the crew members and Captain Wormell, looking for any potential motives for sabotage, mutiny, or piracy.

Additionally, the U.S. Department of Commerce and the Department of State became involved when considering international implications, such as rum-running during Prohibition or the political unrest in some regions the ship had visited.

The U.S. Shipping Board, which had jurisdiction over merchant shipping, also conducted inquiries.

They explored commercial and operational angles, considering the possibility that insurance fraud, piracy for cargo (though the Deering was empty), or disputes over pay or treatment of the crew might have played a role in the crew’s disappearance.

A multitude of theories emerged, both from official sources and the public. These ranged from the plausible to the outlandish—mutiny was a leading theory, suggested by the behavior of the crew when the Deering passed the Cape Lookout Lightship.

Others posited that piracy might have been involved, or that the crew had fallen victim to rum-runners or Bolshevik agitators.

Some speculated that the Bermuda Triangle, a region of the North Atlantic Ocean where a number of aircraft and ships are said to have disappeared under mysterious circumstances, could have been responsible.

This theory, however, was less favored by official investigators who looked for tangible evidence and rational explanations.

The international aspect of the voyage presented its own set of complications.

Captain Wormell had reportedly encountered a man in Brazil who claimed to be a Bolshevik and who threatened that his kind would get Wormell.

This anecdote fueled speculation of a political motive, though it was never substantiated with evidence linking it to the ship’s abandonment.

Despite the exhaustive efforts of multiple agencies, the investigations failed to produce a definitive explanation for the abandonment of the Carroll A. Deering.

The evidence was circumstantial and inconclusive, leading to a final report that was ultimately unsatisfying to those who sought a clear resolution.

In the end, the U.S. government closed its official investigation due to a lack of evidence, and no plausible explanation was determined.

The Carroll A. Deering was eventually declared a loss, with its wreckage salvaged and the case slipping into maritime lore.