The USS Macon, a massive rigid airship commissioned by the US Navy, was renowned for its innovative design, allowing it to serve as a “flying aircraft carrier” by housing and deploying Curtiss F9C Sparrowhawk biplane fighters.

Launched in 1933 and operating primarily from Moffett Field in California, the Macon was a marvel of its time, showcasing the potential of integrating airship and fixed-wing aircraft capabilities.

However, its promising journey was cut short in 1935 when it tragically crashed off the coast of California, marking a significant moment in the history of naval aviation.

Historical Background

Airships, especially rigid airships or dirigibles, were distinct from the more familiar blimps in that they possessed a metal framework covered with fabric, giving them their shape.

The massive size of these vessels allowed them to carry significant payloads, making them attractive for both commercial and military applications.

Germany, particularly, became a leader in the development of these majestic airships with its Zeppelin series.

The successes of the Graf Zeppelin, which made a notable round-the-world trip in 1929, illustrated the potential of airships for long-distance travel and exploration.

In the US, while the commercial possibilities of airships were recognized, it was the military angle that became particularly enticing.

The vast expanse of the world’s oceans made monitoring and defense a challenge for the U.S. Navy.

Traditional ships, while powerful, had limitations in terms of their scouting range.

Airplanes, on the other hand, were still in their infancy and had not yet achieved the long-range capabilities we associate with them today.

Construction of the USS Macon in the Goodyear-Zeppelin Corporation in Akron, Ohio in 1932.

Construction of the USS Macon in the Goodyear-Zeppelin Corporation in Akron, Ohio in 1932.

Airships, with their ability to stay aloft for extended periods and cover vast areas, seemed the perfect solution.

They could act as the “eyes of the fleet”, providing crucial reconnaissance information, and possibly even serving in combat or support roles.

This vision was the impetus behind the investment in airships like the USS Macon.

However, this dream was set against a backdrop of competition, challenges, and inevitable tragedies.

The loss of the British R101 in 1930 and the well-publicized Hindenburg disaster in 1937 highlighted the vulnerabilities of these colossal flying vessels, especially those filled with flammable hydrogen.

These incidents served as stark reminders of the balance between innovation and safety, driving nations, including the U.S., to make critical design and operational choices.

Design Of The USS Macon

Spanning a staggering length of 785 feet, the Macon was among the behemoths of the sky. Its immense size wasn’t just for the awe it inspired but was practical in nature.

The increased space allowed for a more significant payload, extended fuel storage, and subsequently, a longer operational range.

Its structure, primarily composed of duralumin—a light and robust aluminum alloy—granted the airship the required strength and durability.

This metallic framework, when paired with its protective fabric exterior, housed the gas bags and ensured the ship’s integrity against the elements.

USS Macon nearing completion in 1933.

USS Macon nearing completion in 1933.

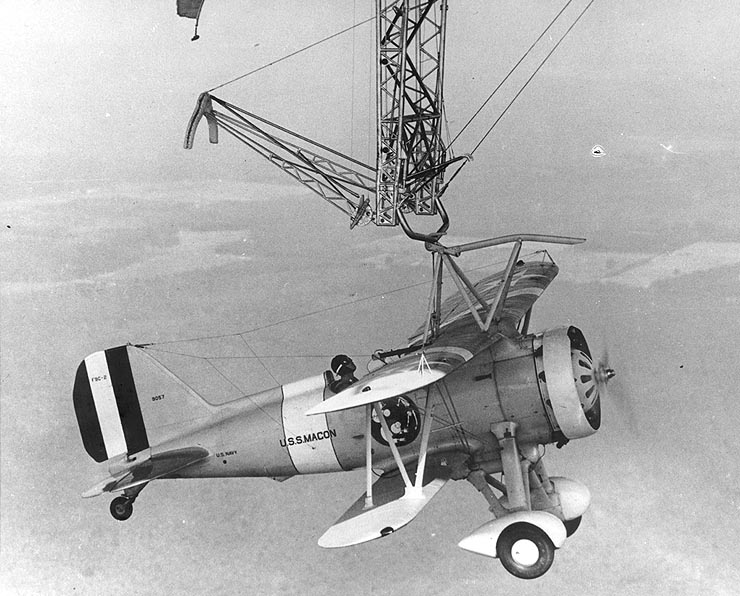

Yet, what truly set the Macon apart was its audacious concept of serving as a “flying aircraft carrier.”

Hidden within the vast expanse of its hull, the airship could comfortably accommodate up to five Curtiss F9C Sparrowhawk biplane fighters. But these aircraft were far from static passengers.

The Macon was equipped with a revolutionary “trapeze” mechanism that allowed these planes to be launched and retrieved in mid-air.

This capability meant that the airship could not only observe vast territories but also deploy or recall defense units as the situation demanded, thereby vastly extending its utility and reach.

Another pivotal design choice for the Macon was the selection of its lifting gas. While hydrogen was commonly used in many of its contemporaries due to its superior buoyancy, it carried a significant risk due to its flammability.

F9C Sparrowhawk attached to the trapeze of USS Macon.

F9C Sparrowhawk attached to the trapeze of USS Macon.

The tragic events of the Hindenburg disaster underscored this vulnerability. In a departure from this norm, the Macon opted for helium—a noble, non-combustible gas.

Although the U.S. largely controlled global helium reserves, the decision to use it for the Macon transcended monopolistic advantages and was rooted in safety, even at the cost of some buoyancy.

Completing the Macon’s innovative design was its intricate navigation and control systems.

Powered by multiple engines that were housed in external nacelles, it had the capability for nuanced thrust direction, enabling maneuvers like hovering or systematic altitude adjustments.

Furthermore, the Macon was outfitted with cutting-edge communication equipment of its time, ensuring seamless contact with terrestrial bases and naval units.

Operational History

Commissioned into the US Navy in 1933, the Macon’s home became Moffett Field in California—a base that would become synonymous with airship operations in the United States.

This West Coast location was strategic, offering vast expanses of the Pacific Ocean for both training and reconnaissance operations. Given the Macon’s unique capabilities, it quickly became a valuable asset in naval operations.

One of the Macon’s primary roles was reconnaissance. Its ability to stay aloft for extended periods allowed it to cover large maritime areas, providing the Navy with a bird’s eye view of vast oceanic stretches—a capability unmatched by traditional naval vessels.

This made the Macon an invaluable asset in naval war games. In these simulated battles, the Macon would often play a pivotal role, acting as a high-altitude observation platform.

It could relay real-time intelligence about the movements, formations, and strategies of “enemy” ships, giving its side a distinct advantage.

USS Macon flying over Manhattan in 1933.

USS Macon flying over Manhattan in 1933.

Beyond structured naval exercises, the Macon was also involved in several cutting-edge experiments. Its ability to launch and retrieve the Sparrowhawk biplanes in flight was a concept that required extensive testing and fine-tuning.

Each successful launch and retrieval was not just a tactical success but also a testament to the seamless coordination between airship and aircraft, reflecting the expertise and training of the crew on both platforms.

This intricate aerial ballet between the massive Macon and the nimble Sparrowhawks captured the imagination of many and became emblematic of the ship’s innovative spirit.

In addition to its military operations, the Macon was also a symbol of American technological prowess and was occasionally showcased in events or demonstrations to the public.

Its sheer size and unique capabilities made it a spectacle wherever it went, often drawing large crowds and media attention.

However, like all pioneering ventures, the Macon’s operations were not without challenges.

Weather conditions, the complexities of managing its onboard aircraft, and the intricacies of navigating such a large vessel meant that every mission came with its share of risks.

Demise Of The USS Macon

On February 12, 1935, the Macon met its tragic end off the coast of California near Point Sur. The airship encountered a severe storm, which caused structural damage to its upper fin.

The damage proved catastrophic, rendering the ship uncontrollable. Despite the desperate efforts of its crew, the Macon descended into the Pacific Ocean.

The tragedy, while immense, saw a silver lining—of the 83 crew members aboard, 81 were rescued, thanks to the quick response of nearby ships and the inherent buoyancy of the Macon’s structure that allowed it to remain afloat for a period after the crash.

The Macon’s demise was a turning point in the American military’s engagement with rigid airships.

The loss, combined with previous airship tragedies, cast doubts on the viability of these mammoth vessels as long-term strategic assets.

In the years that followed, the U.S. Navy’s enthusiasm for rigid airships waned, and focus shifted toward fixed-wing aircraft and helicopters, which were evolving rapidly and offered more predictable operational parameters.

One of the Sparrowhawk fighter planes at the wreckage of the USS Macon.

One of the Sparrowhawk fighter planes at the wreckage of the USS Macon.

However, to confine the Macon’s legacy merely to its tragic end would be an oversimplification.

The USS Macon, in its operational tenure, had showcased numerous technological feats.

Its “flying aircraft carrier” concept, while never fully realized in subsequent military aviation, ignited imaginations and spurred discussions on the integration of different aviation assets.

The principles of launching and retrieving smaller aircraft from a larger vessel in flight influenced later concepts, notably in aircraft carriers’ operations.