The record for the longest-range hit made by a naval warship is a subject that is surrounded by much contention and there are a lot of varying claims.

To narrow it down, it is important to introduce some rules into the equation. Firstly, the shot must have been made in anger from a naval gun on a warship, and secondly, the shot must have been made against a moving vessel which resulted in a hit.

Even then, the results come out rather murky as there are two ships which claim this record. Both of the engagements occurred in June, 1940.

The first record hit was made by the German battlecruiser Scharnhorst against the British aircraft carrier HMS Glorious at a range of approximately 26,000 yards. Then, HMS Warspite hit the Italian Giulio Cesare, again, at 26,000 yards.

Scharnhorst Vs HMS Glorious – The Background

The naval engagement between the German battlecruiser Scharnhorst and the British aircraft carrier HMS Glorious on June 8, 1940, cannot be fully understood without delving into the broader historical and strategic context that enveloped the early years of World War II.

This period was characterized by a dynamic interplay of naval power in the North Atlantic and the Norwegian Sea, where both the Axis and Allied powers sought to assert their dominance and secure vital maritime routes essential for military logistics and economic sustainability.

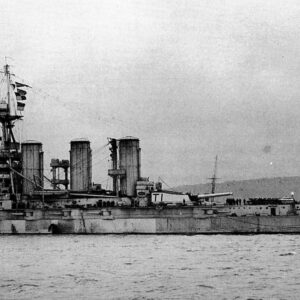

Scharnhorst in port, 1939.

Scharnhorst in port, 1939.

In the lead-up to this pivotal encounter, the Kriegsmarine had been actively engaging in operations aimed at disrupting Allied shipping lanes.

These operations were part of a larger strategy to isolate the British Isles and impair their ability to sustain the war effort.

The Scharnhorst and her sister ship Gneisenau were instrumental in these operations, embodying the German approach of using surface raiders to challenge Allied maritime supremacy.

Parallel to these efforts, the British Royal Navy was engaged in a multifaceted campaign to protect its merchant fleets, maintain open sea lanes, and support ground operations on various fronts, including the Norwegian Campaign. The campaign in Norway, which began in April 1940, was of particular strategic importance.

It represented an Allied attempt to thwart German access to Swedish iron ore and to establish a foothold that could be used to apply pressure on Germany’s northern flank.

The Norwegian Campaign revealed the complexities of combined arms operations and the crucial role of naval power in supporting and sustaining ground forces in a contested environment.

The British deployment of HMS Glorious to the region was part of this larger effort, using the carrier’s aircraft to provide air support to Allied troops engaged in the fighting on the ground.

However, by early June, the strategic situation in Norway had become untenable for the Allies, prompting a withdrawal.

The decision to evacuate Allied forces from Norway was not taken lightly and reflected the broader challenges faced by the Allies in the early stages of the war.

This retreat necessitated the redeployment of naval assets, including Glorious, back to Britain. The carrier was tasked with ferrying RAF aircraft and personnel, underscoring the multifaceted roles that aircraft carriers were beginning to play in naval operations.

The German battleship Scharnhorst pictured in 1939.

The German battleship Scharnhorst pictured in 1939.

The encounter between Scharnhorst and Glorious underscores the importance of intelligence, reconnaissance, and situational awareness in naval warfare.

The lack of aerial reconnaissance and the decision by Glorious to steam without adequate air cover exposed the carrier to significant risk. This miscalculation allowed Scharnhorst and Gneisenau to approach undetected, achieving tactical surprise that would prove decisive.

Moreover, this engagement occurred against the backdrop of a rapidly evolving naval warfare doctrine. The interwar period had seen significant developments in naval tactics and technology, including the use of aircraft carriers and the integration of air power into naval strategy.

The clash between Scharnhorst and Glorious highlighted the transition from traditional surface engagement strategies to more complex forms of naval warfare that incorporated air power as a critical element.

The Engagement

On that day, the Scharnhorst, alongside her sister ship Gneisenau, was patrolling the Norwegian Sea. These ships were part of Germany’s strategy to project naval power into the Atlantic and disrupt Allied shipping. Meanwhile, HMS Glorious, accompanied by the destroyers HMS Acasta and HMS Ardent, was returning to Britain from the Norwegian Campaign.

The carrier was ferrying aircraft from the Royal Air Force, which had been involved in the fighting in Norway. The British flotilla was navigating without the usual air reconnaissance that might have detected the presence of German ships in the vicinity, a decision that would prove catastrophic.

As the German ships spotted the British flotilla, they maneuvered into a position that allowed them to utilize their superior gunnery range.

The engagement began when Scharnhorst opened fire on Glorious from a distance of approximately 26,000 yards, a remarkable feat given the technological limitations of the time.

The Scharnhorst firing her forward guns on HMS Glorious.

The Scharnhorst firing her forward guns on HMS Glorious.

This distance was so great that the curvature of the Earth had to be taken into account for the firing solution. The initial salvos from Scharnhorst demonstrated the effectiveness of German naval gunnery and fire control systems, which were among the most advanced in the world at the time.

One of the early salvos from Scharnhorst found its mark on Glorious, causing significant damage to the carrier. This strike was critical, as it severely compromised the carrier’s operational capacity and eventually led to its sinking.

HMS Warspite – The Battle of Calabria

As World War II escalated in 1940, the Mediterranean Sea emerged as a critical theater of conflict, pivotal for the control of supply lines and the projection of naval power by the Axis and Allied forces.

This body of water, encircled by Europe, Africa, and Asia, has historically been a crossroads of empires and a vital conduit for trade and military campaigns.

Read More The USS Texas ‘Sank’ Herself on D-Day

During the early stages of World War II, its strategic importance was magnified by the competing interests of the British Empire and Fascist Italy, each seeking to secure their naval and colonial dominance in the region.

The British Royal Navy, with its centuries-old tradition of maritime superiority, viewed the Mediterranean as essential for maintaining its global network of colonies and protecting sea routes to India, the Middle East, and the Far East.

HMS Warspite firing on German positions, supporting the landings on Sword Beach.

HMS Warspite firing on German positions, supporting the landings on Sword Beach.

The island of Malta, situated centrally in the Mediterranean, became a key British outpost for launching operations, intercepting Axis supply lines, and providing a critical refueling station for Allied ships.

Gibraltar, at the entrance of the Mediterranean, served as another strategic point, controlling access to and from the Atlantic Ocean.

Conversely, Italy, under Benito Mussolini, harbored ambitions of reviving the Roman Empire’s glory by establishing a dominant presence in the Mediterranean, which he referred to as “Mare Nostrum” (Our Sea).

The Italian Regia Marina was rapidly expanded and modernized in the years leading up to the war, aiming to challenge British naval presence and secure Italy’s supply lines to its North African colonies, where it was engaged in a parallel ground campaign against British forces.

The importance of the Mediterranean was further underscored by the French surrender in June 1940, which dramatically altered the strategic balance in the region.

The French naval presence, previously a counterbalance to Italian ambitions, was neutralized, leaving Britain to face the Axis powers’ naval forces with diminished Allied support.

HMS Warspite in the Indian Ocean, 1942.

HMS Warspite in the Indian Ocean, 1942.

This shift necessitated a reevaluation of British naval strategies in the Mediterranean, focusing on aggressive patrolling, convoy escorts, and the disruption of Axis logistical operations.

The strategic significance of the Mediterranean was not solely naval. The region served as a crucial front for ground operations in North Africa, where British and Commonwealth forces were locked in a seesaw battle with Italian and later German forces led by General Erwin Rommel.

Control of the sea lanes in the Mediterranean directly impacted the ability to supply and reinforce these ground operations, making naval engagements like the Battle of Calabria critical junctures in the broader conflict.

The Prelude to The Battle of Calabria

Following Italy’s declaration of war on the Allies on June 10, 1940, the Mediterranean became an active theater of naval operations. Italy aimed to capitalize on France’s defeat to establish a stronger position in the Mediterranean, seeking to disrupt Allied supply lines to North Africa, where British forces were stationed.

The British, in response, were determined to protect these lines and reinforce their presence in the region, understanding well that the control of Mediterranean sea lanes was crucial for maintaining their overseas empire and for the North African campaign.

The specific catalyst for the Battle of Calabria was a British operation to resupply and reinforce Malta, a strategically located island that was a thorn in the side of Axis supply lines.

Malta served as a base from which the British could launch air and sea attacks on Italian convoys headed to North Africa, making it essential for the British to keep the island well-supplied and operational.

HMS Warspite and HMS Malaya during the Battle of Jutland.

HMS Warspite and HMS Malaya during the Battle of Jutland.

In early July 1940, a convoy carrying vital supplies and reinforcements was organized, necessitating protection from the powerful Italian Navy, which sought to intercept and destroy any Allied shipping in the Mediterranean.

Admiral Andrew Cunningham, Commander-in-Chief of the British Mediterranean Fleet, was tasked with escorting this convoy.

His fleet included some of the most modern and powerful ships in the Royal Navy, among them the HMS Warspite, which would play a starring role in the ensuing battle.

Cunningham’s strategy was not merely defensive; he was also on the lookout for an opportunity to engage and inflict damage on the Italian fleet, thus asserting British naval superiority in the region.

The Italian fleet, under Admiral Inigo Campioni, was similarly prepared to challenge the British effort, setting out with the aim of intercepting the British convoy and engaging the protective fleet.

The stage was set for a confrontation, with both sides aware of the potential for a significant naval engagement that could influence the balance of power in the Mediterranean.

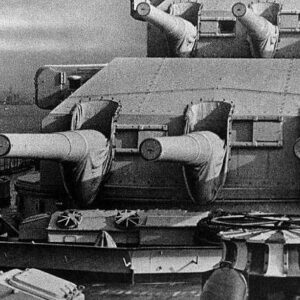

The Italian battleship Cesare during The Battle of Calabria.

The Italian battleship Cesare during The Battle of Calabria.

The fleets moved towards each other, with reconnaissance and air patrols attempting to locate the enemy’s forces and assess their strength.

This game of cat and mouse was complicated by the vastness of the Mediterranean Sea and the limitations of intelligence and reconnaissance technology of the time.

Nonetheless, both fleets eventually maneuvered into position for an engagement south of Calabria, on Italy’s boot-shaped peninsula.

The Battle Unfolds

The British fleet, under Admiral Andrew Cunningham, was tactically withdrawing to the west, a maneuver designed to draw the Italian fleet into the effective range of its heavier guns while maintaining a favorable position relative to the wind and the sun.

This positioning was crucial for maximizing visibility and accuracy for the British gunners while potentially hampering the Italian fleet’s ability to effectively return fire.

The Italian fleet, commanded by Admiral Inigo Campioni, was initially spread out in a broad formation, seeking to maximize its scouting potential and envelope the British forces.

However, as contact with the British fleet was established, the Italians attempted to consolidate their formation to bring their main guns to bear.

The Italian fleet comprised several modern battleships, including the flagship Giulio Cesare, which would soon become a focal point of the engagement.

At approximately 15:53, the battle commenced with the exchange of long-range gunfire. The British battleships, led by Warspite, leveraged their superior radar and fire control systems to engage the Italians at ranges beyond what was traditionally considered effective for naval gunfire. This technological advantage allowed the British to dictate the terms of the engagement from its outset.

HMS Warspite firing on shore positions during the Second Battle of Narvik.

HMS Warspite firing on shore positions during the Second Battle of Narvik.

The pivotal moment of the battle came when Warspite, executing a turn to bring all her guns to bear, fired a salvo at the Italian flagship Giulio Cesare from a distance of about 26,000 yards (23.8 kilometers).

The shot, calculated with the aid of Warspite’s advanced fire control system, struck Giulio Cesare, causing considerable damage and consternation among the Italian fleet.

The Italian fleet, recognizing the danger posed by the British battleships’ superior range and firepower, began to withdraw, conducting a series of maneuvers to disengage while under fire

. The British continued to press the engagement, attempting to inflict further damage and disrupt the Italian fleet’s cohesion.

The engagement off Calabria was characterized by several key factors beyond the exchange of gunfire. Air power played a role, with both sides deploying aircraft for reconnaissance and limited bombing runs against enemy ships.

However, the effectiveness of air attacks on both sides was limited by the high speed and maneuverability of the naval formations and the relatively nascent state of naval air power at this stage of the war.

News

HMS Tiger – The Birth Of The Battlecruiser

HMS Tiger, launched in 1913, was one of the Royal Navy’s battlecruisers, representing the pinnacle of early 20th-century naval design and ambition. Most notably, she participated in the Battle of Jutland in 1916, where the strengths and vulnerabilities of the…

USS Macon – The Flying Aircraft Carrier

The USS Macon, a massive rigid airship commissioned by the US Navy, was renowned for its innovative design, allowing it to serve as a “flying aircraft carrier” by housing and deploying Curtiss F9C Sparrowhawk biplane fighters. Launched in 1933 and…

Liberty Ships – An Icon of American Industrial Might

The Liberty Ships were a class of cargo vessels built in the United States during World War II, designed for quick and inexpensive construction to address the critical need for transport ships. These vessels played a vital role in the…

The German Battleship Gneisenau – A Maritime Powerhouse of the Second World War

The Gneisenau was a German battleship that served as a key instrument in World War II naval operations, undertaking notable missions like Operation Berlin and Operation Cerberus. Commissioned in 1938, she was a symbol of the re-emergence of German naval…

Operation Catechism – The Final Blow To The Tirpitz

Operation Catechism was a decisive Royal Air Force (RAF) mission in November 1944, targeting the German battleship Tirpitz anchored in Tromsø, Norway. Utilizing Lancaster bombers armed with “Tallboy” bombs, the RAF successfully struck the Tirpitz, causing catastrophic damage and leading…

That Time the USS Wisconsin Collided With a Destroyer

On May 6, 1956, the USS Wisconsin, a massive Iowa-class battleship, collided with the USS Eaton, a smaller Fletcher-class destroyer, during a training exercise off the coast of Norfolk, Virginia. The collision occurred as the Wisconsin was executing a turning…

End of content

No more pages to load